Adding shipping to the UK ETS could help push the sector towards decarbonisation — but there are concerns that the carbon price is still too low to make a dent and that it creates a patchwork of regulations in a market where international measures are also in the pipeline.

UK ETS and Shipping: An Overview

The British government closed a public consultation this week on its plans to extend the national Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) to domestic shipping from 2026. It will start with vessels over 5,000 gross tonnes (GT), which are already obligated to monitor, report, and verify their emissions.

The measure is generally welcomed as an additional tool to push the hard-to-abate maritime sector to decarbonise and widen the impact of the EU ETS, which was extended to ships entering the bloc’s ports last year and will extend to offshore vessels in 2027.

For the industry, the concern is how the UK obligations will fit with global economic measures in discussion at the UN’s International Maritime Organization (IMO), as well as the EU scheme.

“Whilst we support the proposed ETS expansion in its aims to incentivise decarbonisation, aspects of the current proposals present challenges to the industry and could undermine wider government aims,” the UK Chamber of Shipping told Carbon Pulse by email, without going into further detail.

“The proposals should seek to avoid possible market distortions by diverging from existing EU measures.”

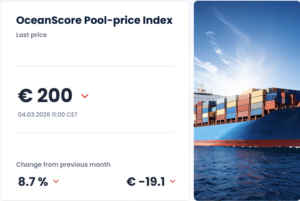

For others, the worry is that UK carbon prices are just too low to push the sector off cheaper fossil fuels. UK Allowances are currently hovering in the low £30s per tonne, compared to around €80 for EU Allowances.

“It’s unhelpful policy, and that’s quite rare for me to say because normally I’m quite pro-policy and regulation,” said Tristan Smith, a professor of energy and transport at University College London, referring to shipping’s potential inclusion in the UK ETS.

The problem is that a carbon price of £100, which analysts forecast as coming by the end of the decade, is still too low to make synthetic fuels derived from clean electricity economically competitive, he added. Synthetic fuel, in particular, requires a carbon price of £250-300.

“It’s a price that costs money, because it’s still going to add £300-400 to the cost of every tonne of fuel, because there’s about 3 tonnes of CO2 in every tonne of fuel. But it doesn’t close the business case to a hydrogen-derived fuel.”

Nonetheless, extending the ETS to maritime does bring a highly polluting sector under the ‘polluter pays’ principle, said Jon Hood, manager of UK sustainable shipping at the NGO Transport and Environment (T&E).

According to T&E’s modelling, it sets a price signal that begins to close the cost gap between fossil fuels and clean alternatives such as renewable hydrogen and methanol. It also nearly halves the gap for onshore power supply.

“This should begin to support decarbonisation, and all the more so if government chooses to invest the ETS revenues in greening the sector,” Hood said.

“Far from penalising shipping, this measure begins to correct a decades-long, market-distorting subsidy of the shipping sector which has benefitted from zero fuel taxation and zero emissions pricing.”

ETS sets sail

The UK’s shipping sector accounts for around one-fifth of the country’s transport emissions, and around 3% of total greenhouse gases.

The government plans to begin by applying the ETS to domestic maritime voyages, defined as beginning and ending in UK ports. It would include CO2, methane, and NO2 emissions. This is done in order to avoid what it called “perverse incentives” for fuel that’s lower in CO2 but higher in the other greenhouse gases.

To make room for the sector, the government is proposing to raise the market’s cap by 2.4 million allowances per year between 2026-30, in line with its delivery plan for the legally-binding Carbon Budgets, according to the consultation. This assumes “limited abatement” of maritime emissions in the 2020s and significant savings from the early 2030s.

Registered shipowners would be obligated to comply with the ETS, unless the owner decides to delegate it to the company in charge of ensuring the ship complies with the International Safety Management Code.

It is also proposing to review the threshold from 2028, looking at how it’s working for vessels over 5,000 GT and the practicalities of carrying out monitoring, reporting, and verification for vessels of 400-5,000 GT – with an eye to potentially expanding the ETS further to smaller vessels.

But while the overall move is welcome, there are problems with the government’s proposal, according to T&E.

In particular, the decision to exempt emissions from international voyages creates a “massive, unfair loophole” for which the UK would miss out on £750 mln per year in much-needed revenues, Hood said. Exempting the Crown Dependencies — Isle of Man, Jersey, and Guernsey — would also allow vessels to avoid the ETS by sticking to the Channel Islands.

The cap on allowances should also be based on the sector’s actual emissions in order to drive reductions, he said.

Beware the patchy seas

For the shipping industry, one of the biggest concerns is that this creates a patchwork of climate policies in a sector that spans global waters, including a mis-match with the neighbouring EU ETS.

“The UK should be at the centre of global decarbonisation agendas,” the UK Chamber of Shipping said. “With the EU ETS scheme entry into force for offshore vessels in 2027 and economic measures expected to be adopted by the IMO this spring, it is essential that any UK scheme recognise and align with international frameworks, to avoid regulatory fragmentation.”

The British government is also wary of doubling up on regulations, and asked for views in the public consultation on whether it should eventually extend the ETS to international shipping if the IMO measures are delayed or insufficient.

“The UK government still considers that the primary route for addressing international emissions from shipping remains multilateral action taken at the International Maritime Organization, where we’re supporters of high ambition in the development of mid-term measures,” Matthew Ball, of the Department for Transport (DfT), told a webinar presenting the consultation in December.

The IMO’s 175 member countries are expected to approve new emissions reduction measures at a meeting in London in April. But while a number of countries are pushing to introduce an annual levy on greenhouse gas emissions from shipping, several others are opposed. The UN body needs consensus to go ahead.

The UK is also looking at ways to avoid double charging for emissions in the Irish Sea, where it butts up against the EU ETS. It has proposed to either reduce the UK ETS obligation to half for vessels travelling between Northern Ireland and Britain, in line with the EU obligations, or to expand the scope of the UK ETS to 50% of emissions for journeys between the UK and the European Economic Area (EEA).

For ships already sailing through the EU ETS, the addition of a UK carbon price should not be difficult to handle as long as the UK sticks close to its neighbour’s rules and technicalities, said Albrecht Grell, managing director of OceanScore, which provides compliance and data solutions to the industry.

“You’ll hear loud screams and shouts about it. But in reality, if the mechanics of the rules are somewhat similar to the EU’s, then the data flows and processes and systems used for it will be similar,” he said.

That means that as long as the UK asks for the same data that companies already provide the EU, they can just send it to both authorities — as well as to other countries that are looking to impose a carbon price on shipping, such as Turkiye and China.

“If it’s based on the same CO2 emissions, or CO2-equivalent emissions, this data is already available and it’s just another detour,” he said. “Shipping won’t like it, but I think it’s doable.”

The UK should also be able to avoid the data, contracting, and administrative complications that shipping companies experienced in the first year under the EU ETS, as long as it has one central place where companies open their accounts, Grell added.

Alternate Routes

Whether they are supportive or sceptical of adding shipping to the ETS, experts widely agreed that the carbon price alone will not be enough to fully decarbonise the sector.

The government published a plan back in 2019 for reaching net-zero shipping by 2050, but it has yet to establish the regulations needed to follow it.

A clean fuel mandate, which was suggested in the plan, could give ship owners and operators a clear, long-term trajectory for the transition and strengthen the business case for clean alternatives, said Smith.

As well as clean fuels, the sector desperately needs electrification — there, the problem is with the UK’s clogged electricity grid.

Ferry routes between Dover and Calais and in the Hebrides, for example, could cost-effectively switch to battery power, he said. “There are lots of ports that would love to provide electrification, but they’ve put requests in and are being told they’ve got five years or more before they can have the connection.”

On top of that, the UK could follow the EU’s example of mandating that ships over 5,000 GT use onshore power supply for their energy needs while at berth, in order to reduce emissions from their auxiliary engines when in ports. This, however, could be delayed by the difficulties of securing consent for grid connections in the UK.

But in the meantime, the government can strengthen the impact of ETS on shipping by putting the revenue to good use, experts agreed.

“My main advice is to ring-fence at least a portion of the revenues that are generated from £100 on shipping emissions, and to be very transparent about the hypothecation of that ring-fencing,” Smith said.

“That’s the only thing that provides certainty to the market to go ‘OK, this is a government that is actually wanting an energy transition, and on that basis, I can invest with confidence.’”

This article was originally published on Carbon Pulse.

By Sara Stefanini